Crystals and careers

How research is turned into business

New technologies require one thing above all else. They take time. It takes years for a good idea to grow into a viable spin-off,” says Thomas Schröder, director of the Leibniz Institute for Crystal Growth (IKZ) in Adlershof. For him, patience has paid off. In the current evaluation period, his institute boasts no fewer than four new start-ups. That’s quite a feat, given that spin-offs from IKZ are generally the exception rather than the rule. Normally, the knowledge developed here flows directly into existing industrial partnerships. “Our classic form of technology transfer happens through companies that are already established on the market,” he says. If there is not suitable partner for a new technology, he and his team try to turn an idea into a spin-off.

The big stars at IKZ are high-performance crystals. “The materials we develop here are the basis for electronics, photonics, and even quantum research,” says the institute’s director. Many technological innovations—from quantum chips to high-power lasers—are built on them. IKZ does not see itself as a supplier of finished products, but as a facilitator.

The research teams develop crystalline materials tailored precisely to new applications. This means: Creating novel materials and developing complex production processes in years of preliminary work. Yet it’s precisely this complexity that makes IKZ so attractive to research-driven start-ups. “We can give young entrepreneurs something tangible that they can use to make real progress,” says science manager Maike Schröder.

This isn’t only about knowledge—it’s also about the machines. “The systems we use to produce our materials are extremely expensive,” she says. “A start-up in an early phase can rarely afford this.” That’s why the institute supports founding teams during the transition period, not just with advice and lab capacities. Through suitable contractual arrangements, it also provides access to equipment and infrastructure—a form of start-up support that is otherwise hard to obtain.

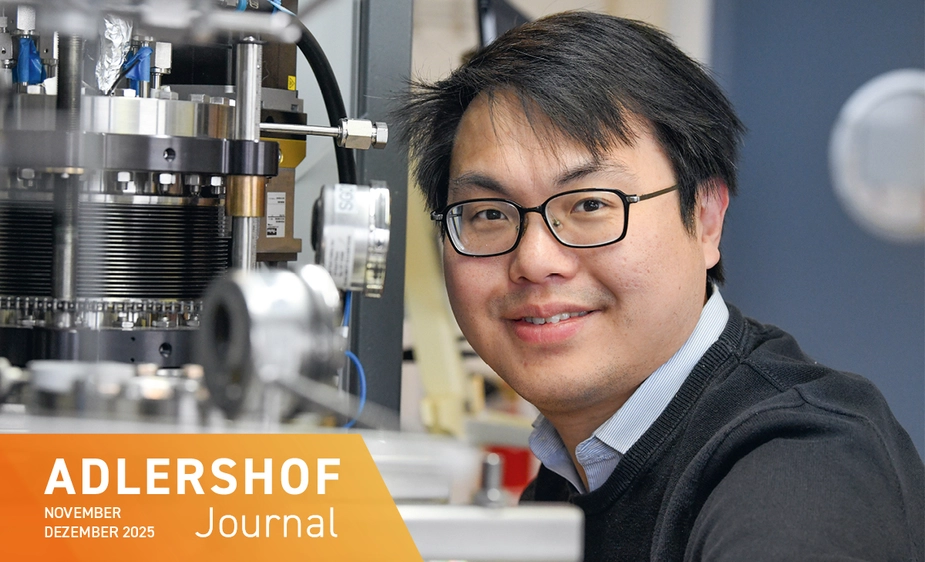

A good example of this is the start-up NextGO Epi. The company produces high-quality gallium oxide layers, a material seen as a promising candidate for high-performance electronics. “We’re standing on the shoulders of giant,” says founder Ta-Shun Chou. He benefits not only from the research conducted at IKZ but also from its infrastructure, network, and the fact that the institute can provide not just gallium oxide layers but also the matching substrates. Such close collaboration between a research institute and a team of founders is rare in Europe.

The company’s founding was anything but a sure thing. “Normally, our doctoral students leave the institute after completing their PhDs,” explains Thomas Schröder. “We train them for research and development positions in academia and industry.” However, when the magic word “start-up” comes up in connection with a convincing idea, it is possible for young researchers to receive follow-up funding. And enough time to turn their plans into reality. This is how it went with NextGO Epi. Today the company is working on technologies to be applied in future high-voltage applications, such as fast-charging stations and energy transmission from wind and solar parks. The institute supports Chou in administrative matters, among other things, which range from patent research to export control. But, to him, one thing matters more than anything: time. “If we don’t move fast to realise our ideas, the competition will.”

Indeed, time is a decisive factor for everyone involved—whether those doing the research or those building businesses. Materials need time to develop, start-up ideas to mature, and products to reach the market. “Science is always a global race,” says Chou. But even though processes take years, they have to start somewhere. IKZ can provide the fertile ground for this. Thomas Schröder is thinking one step ahead: He hopes to build up another start-up from within the institute, one focused on crystal growth. “No one in Europe can do what we do here,” he says proudly. “But if Europe wants to remain technologically sovereign, that expertise must also translate into industrial value creation.”

Kai Dürfeld for Adlershof Journal