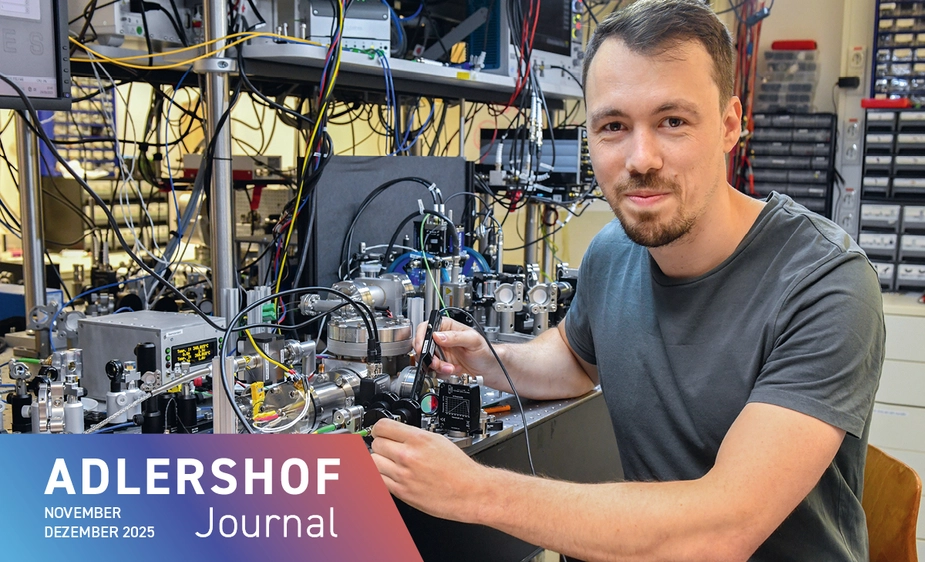

The timekeeper

Oliver Fartmann is working on an improved atomic clock

What are the paths into science and research? “I was quite good at maths, I think,” says Oliver Fartmann. Good enough, at any rate, to catch the attention of his physics teacher at the Archenhold Gymnasium in Niederschöneweide. In year seven, he recommended he take part in Jugend forscht, Germany’s preeminent young science competition.

At first, the challenges were manageable. Fartmann and two classmates dropped metal balls from different heights and measured the dents they made in polystyrene to calculate their potential energy. Later, the tasks became more demanding. They began developing a thermometer using laser. This, Fartmann fondly remembers, “went moderately well.”

He took part in Jugend forscht every year until his A-levels, gaining insights into ever more advanced realms of physics. At thirteen, he shadowed researchers at the German Electron Synchrotron, or DESY, in Zeuthen, where they work on tracking down cosmic particles. Fartmann was so enraptured by this that he returned a year later for a two-week internship. As a high school student, he spent two further research stays at CERN—the European Organisation for Nuclear Research near Geneva, home to the world’s largest particle accelerator.

For almost ten years now, he has been developing “all kinds of sensor based on atoms” at the Joint Lab Integrated Quantum Sensors in Adlershof. At first glance, all this might seem like a straight-line career path for a born atomic physicist. However, Fartmann prefers a different reading. There was never a master plan, he says, that led him to Humboldt-Universität’s Department of Physics, which operates the Joint Lab with Ferdinand-Braun-Institut, Leibniz-Institut für Höchstfrequenztechnik (FBH).

He says it was “more by chance” that he applied for a student assistant position at the Joint Lab Integrated Quantum Sensors, where he met “some really nice people” and decided to stay not least because of them. There he went on to complete both his bachelor’s and master’s theses. He spent the last six years finishing his doctorate, dedicated to refining a precision technology that’s more than seventy years old: the atomic clock. With his approach, the timekeeping rhythm is upheld by the oscillation of laser light waves interacting with a cloud of atoms enclosed in a vacuum. This is known as an optical atomic clock. Owing to the vastly higher frequency of the laser light, it achieves a thousand times the accuracy of a conventional atomic clock, which relies on electromagnetic microwaves as its time base. Fartmann’s clock measures time to fourteen decimal places—he is striving for fifteen.

A key aim of his research is to develop compact, robust devices that work reliably outside the laboratory. Such portable optical atomic clocks are still rare. Fartmann has presented his work on atomic clocks at the Adlershof Science Slam numerous times. He is a big fan of the format’s fundamental idea of “bringing scientific topics to a lay audience in a humorous way.” To him, sharing knowledge is close to his heart, as is his work as a youth coach at his chess club, SV Mattnetz.

Born near Munich, the now 30-year-old moved to Berlin when he was twelve years old. He grew up in Altglienicke, attended secondary school in Schöneweide, studied in Adlershof, and plays chess in nearby Plänterwald. Fartmann’s academic path has stayed within a fairly compact radius. In the end, it was love that made him venture beyond Berlin’s Southeast. He now lives with his girlfriend in Lichtenberg.

Dr. Winfried Dolderer for Adlershof Journal